THAR: The sunflower plantation disappears. It is replaced by thorn bushes and starved camels. Women, children and men dot the roads with their cattle as they walk to safer places in search of food, water and employment. The change in landscape is stark — lack of water has shriveled everything at Tharparkar.

This is not the first time a drought has occurred. As recent as in 2007 another drought hit the only fertile desert of the world. “There was another in 2005, 2004, 2001, 1999, 1996, 1995, 1987, 1988, 1985, 1979 and 1968. But this time the situation is much worse,” said Pardeep Kalani, a social activist in the area.

The Mitti Civil Hospital, the only hospital in the entire district, is restive today. The army is here guarding the run down white building. Politicians arrive in Land Cruisers followed by police mobiles — their sirens blare rudely on the cobbled streets pushing pedestrians to the roadside — they bring with them relief goods and a barrage of reporters — who take pictures as they distribute food to their voters who they had forgotten till the loss of lives made headlines.

One hundred twenty five people died, seven in March. At the intensive care unit malnourished babies lie in beds. Some are kept inside incubators which locals call ‘sheeshay ka dabba’. Their mothers sit at their sides. They look wasted. “Malnourished mothers give birth to malnourished babies and so the cycle continues,” explains a doctor.

The former head of the hospital was sacked last week. A new one arrived. “We need incubators, medicines and a team of qualified doctors,” he states. There is something wrong with the diagnosis patients are receiving. While Kuldip Bachu, 25, complains of pain in her joints, breathing difficulty and severe headache, the doctors told her it is just a stomach-ache. “We are falling sick because of the water we drink,” she says.

When the drought comes their only source of water dries up. “Water in the wells goes down to a hundred feet. We tie pillows to our buckets and pull out water. But the water we get is salty,” said Kavita, a local.

It is mainly small-scale farmers who are dying of the drought. They live in thatched huts and grow crops for a living. The desert becomes green when it rains. But lack of water has pushed it into its present state.

When the British ruled Tharparkar they had set certain rules. If by August 15 every year there was no rain, emergency was to be declared in the region. Thereby efforts to relocate families and release food stocks were to be made.

The Sindh government was following the 300-year old policy — only with much less efficiency. There was moderate rainfall in September and so the government pushed the announcement to much later.

The godown at Mithi is stocked with 11,000, sacks of wheat. But it was not until Saturday that food was released. By then scores of lives had been lost. “We work for the food department. Our duty is to stock goods. We cannot release anything till the revenue department tells us to,” says the in-charge as he directs workers to load a truck, which has just arrived.

Top PPP leadership gathered at Thar in the last few days. They included Bilawal Bhutto, Qaim Ali Shah, Sharmila Farooqui and Rubina Qaimkhani. As part of long term strategy to empower the forgotten desert it was decided that every week a tanker will bring water to the drought affected areas.

But what about a permanent solution? “No pipeline for water can be laid in these areas. The population is scattered in small pockets every where,” said a spokesperson for social development minister Rubina Qaimkhani.

The National Disaster Management Authority seems cold. “The media is flaring up the numbers. It is an annual phenomenon. Twenty-one babies died. We have announced a Rs77crore food package,” said a statement released.

As the car prepares to leave for Karachi, a group of ten-year old boys see the PPP flag on the Land Cruiser leading the caravan. “Jiyay Bhutto,” they roar, oblivious of how their leaders have failed them again.

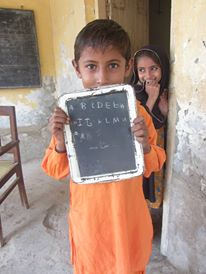

Tharparkar does not need aid in the form of wheat or water. It needs a socio-economic overhaul — education, employment, empowerment and awareness to choose better leaders. As Amartya Sen, nobel laureate puts it— “no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy.”

originally published here