Karachi

Salma Jaffar, 35, lies on a stretcher, barely able to talk to her relatives on the cell phone.A bullet had pierced her chest and another one her arm just as she was releasing polio vaccine from a dropper into a child’s mouth in Qayyumabad, a locality with mixed ethnicity.

She saved her life and that of the child who was in her arms by jumping inside the house. But three other members of her team, Anita Zafar, Akbari Begum and Fahad Khalil, were unable to survive the barrage of bullets fired by four men who had come on two motorcycles. A passerby, Ali Asghar, also suffered injuries.

The brazen attack on Tuesday not only jeopardised anti-polio efforts in Karachi, but in the entire province. The vaccination campaign has been suspended for now. Polio workers have also refused to participate in the immunisation campaign across the province until they are provided with adequate security.

Unfortunately, Pakistan is one of the only three countries in the world where polio remains endemic, along with Afghanistan and Nigeria. One of the major reasons for this is the series of Taliban attacks on vaccinators.

The Taliban oppose anti-polio campaigns saying that they are some kind of a “sinister plot to sterilise Muslims”. The World Health Organisation had recently warned that Peshawar was the world’s “largest reservoir” of polio virus.

Seemin Jamali, the in-charge of the Jinnah Hospital’s emergency ward, said the three polio workers were already dead by the time they were brought to the hospital. “The passerby suffered minor injuries and has been discharged, while Salma is still undergoing treatment,” she added.

No security

The biggest question that is being raised following the Qayyumabad attack is about the lack of security for the vaccinators. Korangi Town Health Officer Dr Syed Hussain said the team started off their duties without any security protocol.

“Police were unavailable till 11am, and we thought the area was safe,” he added.

Qayyumabad has a mixed population including Mohajirs, Sindhis and Pakhtuns. “This wasn’t a troubled area like Gadap or Sohrab Goth where vaccinators are attacked. There has never been any problem in this locality during [the previous] anti-polio campaigns,” said Hussain.

Polio vaccinators usually face resistance in the Pakhtun-dominated areas of the city where the Taliban have a significant presence.

The Qayyumabad attack was the first incident of its kind reported in District East of the city.

SSP East Muhammad Shah said police had told the town health officer that the team should not be dispatched before a police van reached there at 11am.

“There has been an increase in reports about extremists gaining a foothold in the area,” he added.

“The standard operating procedure is that all polio teams should leave with security protocol.”

What next?

The attack has left polio workers, who were already worried about their security, more frightened and demoralised. Mazhar Khamesani, the in-charge of the Expanded Programme on Immunisation Sindh, said the anti-polio drive had been suspended in the province until further notice.

He demanded proper security steps for all polio workers in the province. “The morale of our workers has reached its lowest ebb.”

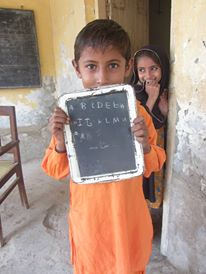

Khamesani said almost 80 percent of the workers were volunteers hired from nearby localities for Rs250 a day with a target of vaccinating 150 children.

Dr Ashfaq Ahmed, a health officer in North Nazimabad, said the attack would make it very hard to motivate vaccinators to continue participating in the campaign.

Muhammad Saeed, who supervises polio teams, said the vaccinators, most of whom were women, were being pressured by their families to stop working because of the dangers involved.

Fatima Ali, a polio worker, said she and her colleagues are labelled brave soldiers, but the fact was that they were just looking to earn some extra money.

“We cannot risk our lives only for a few rupees.”

Seven polio cases were reported in Karachi last year. The Taliban and fundamentalist religious groups propagate that the American CIA is behind the polio vaccination drives as part of a conspiracy against Muslims.

To counter them, aid organisations have distributed pamphlets continuing 24 fatwas in favour of the anti-polio campaign in localities where the vaccinators face resistance, but the attacks continue.

The Sindh chief minister announced Rs500,000 each in compensation for the polio vaccinators slain in Qayyumabad.

Abdus Sattar Edhi, the octogenarian social worker, announced compensation of Rs100,000 for the families of slain health workers.

picture courtesy The News

story originally published here