Karachi

In Sindh’s Jamshoro district, there are pockets with zero percent literacy. But at a school run by a not-for-profit organisation, a group of 20 students, mostly girls, are trying to change the status quo.

They know everything about Article 25a—the right to free and compulsory education for children aged from five to 16; the fact the constitution recognises education as a fundamental right now — a right that citizens are born with; and that if parents don’t send children to school they can get imprisoned for three months.

In their village, they have held theatrical performances to increase awareness about the law. They have visited parents. They have even talked to government teachers, one of whom is now tackling the problem of absenteeism at his high school by writing letters to parents whose children are not attending.

A boy died in their village while crossing the highway to reach his school on the other side. He was run over by a truck. The girls wrote a letter to the district’s education officer to tell him about this very important issue.

“Education is our right. If the authorities do not give us our right, we should pester them until they succumb,” says Shehla, a vocal ninth grader. And how do you pester the government? “We write letters; involve the media; and hold peaceful demonstrations,” she says.

This is a small community mobilisation campaign that the Indus Resource Centre, a not-for-profit organisation, is running at three of its schools in Jamshoro. While this may be a ray of hope, the larger picture is somewhat bleak.

A year after Sindh became the first province to guarantee education as a fundamental right to its citizens, not much has been done on ground. A visit to rural areas brings out a dismal picture of public schools.

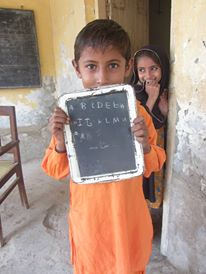

Against promises by successive ministers of introducing technology in education, students can still be seen using slates and chalk. At a higher secondary school in Kotdiji, a village in Khairpur, there are only two teachers against the needed 22. Not surprisingly, students don’t bother to attend school.

In Habibullah Goth, another downtrodden village, a new school building has been constructed in front of an empty school building. While the former enrols about 10 students, villagers don’t know the last time classes were held.

Many girls interviewed during the visit accepted that their parents did not allow them to go to high school as boys from other villages sat in the same classes.

Nutrition remains a problem and during recess many students run home for a quick snack. “Generally they come without breakfast. And sometimes after they leave school for lunch they don’t come back,” said a teacher present at one of such schools.

A pilot project by a milk company and a private school where students are given a cup of milk for everyday attendance has shown remarkable improvement in turnout, claim teachers.

No official notification has been dispatched to office-bearers at the provincial education department, informing them about the legislation for free and compulsory education. As a result, only 25 percent officials in rural Sindh know about the existence of such an act, states a study conducted by the Indus Resource Centre.

The study titled “Implementation of the Sindh Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act” also states that only two percent parents in rural Sindh know about the year-old law. Similarly, only two percent of school-going children in rural Sindh know about the law. Among the teachers a mere three percent know the law.

Thirty-two percent of children in Sindh are out of school, according to the Annual State of Education Report 2012.

While the Sindh government took the lead in making education free and compulsory, there is a need now to make schools a fun place to learn. This can only be achieved through addressing the hurdles communities face in accessing education.

It is not that there is no demand for education. Schools run by the social sector are often full to the brim while public sector schools are plagued with low attendance. It is time the Sindh government takes the lead in bringing children back to school.

originally published here