Karachi

A government school and an O-level school are two extremes of the stratified education system that exists in the country – which one of them will children end up in depends on how much money their parents have.

A rough estimate of the various layers that make up urban education brings forward eight categories of parallel systems that have been functioning for years – Madrassahs, government schools, English-medium schools, cadet schools and colleges, O- and A- level schools, the Aga Khan University board, government colleges and public and private universities.

In the absence of any formal tab, each of these schooling systems devises a different curriculum and fee structure.

As a result, each institute attracts a certain social class, and year after year, churns out batches of students, who share life experiences completely alien to each other.

According to a survey titled ‘Education in Pakistan’ conducted by the Strengthening Participatory Organisation, “Madrassahs, Urdu- and Sindhi-medium schools and English-medium schools cater for different socio-economic classes and further increase the alienation that exists between them.

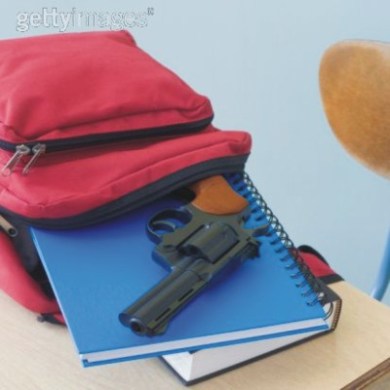

The system is unjust as it distributes the most lucrative and powerful jobs advantageously to the elite, which is educated in English-medium institutions. Meanwhile, the Madrassah-educated people and those who fail in Urdu-medium schools join the increasing army of the unemployed, who use the idiom of religion to express their defused sense of being cheated of their rights. Hence, the unjust system of schooling might increase Islamic militancy in Pakistan that will be as much an expression of resentment against the present policies of the ruling elite as the commitment to Islamising the society.”

Professor Jaffer Ahmed, the director of the Area Study Centre for Pakistan Studies, has a similar perspective. “The stratification in education is creating two nations within the country with no communication bridge.”

Officials in the education department say there are 2,800 government schools in Karachi. Private schools are even greater in number. “There are about 6,000 registered private schools, and a conservative estimate will reveal that there are 4,000 unregistered private schools in the city,” said Syed Khalid Shah of the All Private School Management Association.

Education at government schools comes free of charge, but the standards are such that even a poor man prefers to send his children to a small-scale private school.

In survey carried out by the Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi titled “Urban Trends in Education”, it was discovered that only 34.8 percent fifth grade students at government schools in Karachi could read English sentences and solve three-digit division sums. Only 47.8 percent of them could read an Urdu storybook.

The figures for fifth grade students at private schools were relatively higher, but not satisfactory as 51.4 percent could read an Urdu storybook, 91.4 percent could read English sentences and 62.9 percent could solve three-digit division sums.

The same survey also pointed out that the disparity among private and public sector schools was the highest in Karachi in comparison with Lahore and Peshawar. Of the total percentage of students enrolled in schools, 26.5 percent attended government schools and 70.8 percent private schools.

A brief history

According to the state policy, taxes should be spent on educating students in Urdu and Sindhi languages only. This had been the practice in schools which operated in the 60s and 70s. Teaching continued in the mother tongue till fifth grade, after which it was carried on in both English and Urdu.

It was stated in the Strengthening Participatory Organisation survey that it was during Ayub Khan’s time that cadet colleges were first constructed. The medium of instruction there was English, and the reason given for the armed forces to step into the field of education was the “need to produce officials, who could step into the military bureaucracy”.

These institutes provided education at a subsidised rate, and were situated in state-of-the-art buildings. After nationalisation in 1972, the standards of government schools suffered a serious blow. It was then that O-and A-level schools began to spread. The market gap for quality education was captured by a number of private schools of all sizes that mushroomed in the city.

On the other hand, the Madrassah is an educational institution that exists with every other mosque, even in remote villages with no schools.

More often than not, parents send their children to these ‘boarding schools’ to ease the burden of extreme poverty.

The Aga Khan Board was introduced in 2003, and offers both matriculation and intermediate education. It follows the national curriculum and claims that its fee is “less than one-third of O- and A-level schools” but the standard is the same.

Pakistan might be the only country with an education system as layered as this and produces children completely alienated to each other. Here, one child has no bench to sit in a classroom and the other has access to lush green football stadiums. In a situation like this, one is forced to asked that if the constitution guarantees that all citizens equal, why are some more equal than others?